In the second in a series of articles on biodiversity and real estate, John E Fernández and Thomas Wiegelmann explore what cities can do

People originally settled into groups and founded cities for various reasons, sharing labour and collective efforts gathering resources, producing goods and services, maintaining security from wild animals and marauding neighbours, establishing seats of political and religious authority and concentrating scholarship and cultural activities. Decisions on the location of a new city considered availability of water, game for hunting, arable land for agriculture and useful materials like metal ores for tools and minerals such as clay for pottery and bricks. Unfortunately, the founding of a city has always been detrimental to local biodiversity.

Modern cities attract the majority of the global population and provide essential services to vast numbers of individuals, generating employment opportunities, stimulating innovation, and propelling economic progress and cultural exchange.

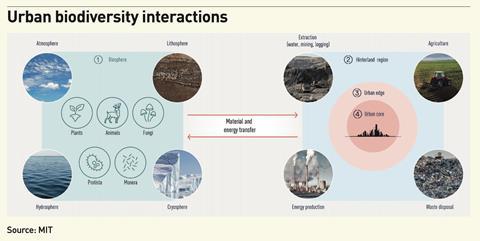

Cities interact with biodiversity in a variety of ways, and at a range of temporal and spatial scales. Specifically, one can identify four zones in which cities affect biodiversity directly and indirectly.

At the largest scale, cities affect the entire global biosphere – the totality of the many regions of Earth in which life exists, including the atmosphere, hydrosphere (oceans and rivers), lithosphere (land) and cryosphere (the Arctic and Antarctic). At smaller scales, a city affects the region around it, the hinterland primarily through extraction of resources. At the outer extent of the city in the zone between dense population, a concentration of housing, infrastructure and urban sprawl is the urban edge. As the city extends its area, this edge exerts pressure on local species and habitats. And finally, within the city itself, biodiversity is most challenged by the ubiquity of impermeable surfaces, buildings and hard infrastructure like roads and all other urban elements that eliminate suitable habitats and critical resources that non-human species depend on. We will focus on the actions that cities can take in each one of these zones to enhance biodiversity.

First, at the scale of the biosphere, cities that are actively transitioning to efficient building and transport systems, low-carbon energy production and consumption, waste reduction and circular economies, limits on plastics and many other sustainable strategies substantially relieve pressure on global biodiversity. In fact, the collective actions that cities take to address climate change by transitioning aggressively to a net-zero carbon future will result in the greatest positive effects on biodiversity of any of the four scales described in this article. These local actions have enormous impact across the globe. Of particular importance is the transition away from fossil fuels. Because urban economies dominate the global demand for resources, any significant lessening of the demand arising from cities – its industries, residents, infrastructure and more – substantially lessens the pressure on the world’s ecosystems.

Second, the immediate region within which a city is located and draws resources is the hinterland. Local agriculture, mining of minerals especially for building construction and logging of wood are just some of the activities that feed the local city from this rural region. Cities that are disconnected from their hinterlands and consider regional land only in terms of its market valuation tend to undervalue ecosystems and species native to the region.

Therefore, it is important for hinterlands and cities to be connected symbiotically, prioritising the economic and environmental health of the totality together. Research from the Stockholm Resilience Center highlights three elements of productive and sustainable relations between cities and their hinterlands: investment in diversity that supports local food production and other resources while designing green, blue and gray infrastructure to be more resilient and flexible; managing connectivity between cities, wildlife corridors and important habitats; better communication between various actors and stakeholders in creating social trust and collaborative opportunities between rural and urban conditions.

Therefore, sustainable local agriculture serving urban markets, restaurants and residents of a city within a particular region can enhance coexistence with biodiversity. Policies and investments to set aside as much of the region for biodiversity can be supported by the local urban economy. Even campaigns to heighten the awareness of city residents of the benefits of a healthy region for the city and beyond can be important to drive momentum for conservation.

Also, global municipal solid waste now amounts to more than 2bn tonnes annually, degrading and threatening regional ecosystems with plastics, toxic and forever chemicals, and hazardous materials. Cities can substantially improve the health of global and local biodiversity by severely curtailing waste dispersion into the environment and developing multi-scalar circular economies across industries and household consumption.

Third, the urban edge of many cities is a zone of transition, and sometimes in contention, while offering important opportunities for stabilising and enhancing habitats and resources important to local biodiversity. Cities tend to expand driven by economic and population growth. Between 2015 and 2050 the global urban footprint is expected to expand by up to 1.3m sqkm, an increase of 171%.

Some cities are taking action to protect ecosystems at the edge of cities while stabilising the urban spatial extent. One strategy is an urban growth boundary, a land use planning limit that attempts to control urban expansion. Portland Oregon in the US has an established urban growth boundary that has proven to be an effective limit to unfettered growth, although it has been expanded three dozen times since its implementation in 2007. A particularly effective method for limiting urban growth is a hard limit on the provision of urban services, power and water beyond a certain line.

Also important at the urban edge is the creation of habitat corridors and greenways that can help to connect fragmented habitats and provide pathways for wildlife to move through and between urban areas. This can be accompanied by the restoration of natural areas such as wetlands, forests, and rivers to provide habitat for wildlife and improve biodiversity.

Fourth, within the space of the city – the urban core – the challenges to biodiversity are many and varied. From the hard surfaces of roads and buildings to the barriers imposed by highway walls and networks of infrastructure to the various sources of heat, artificial light and noise, cities impose existential threats to species of every kind. In the urban core, habitats and sources of food are nonexistent or significantly degraded and local ecosystems have completely collapsed.

In urban core there is much that can be improved and many new actions that can be taken to enhance biodiversity. Research shows that cities can provide important habitats for a wide range of species, including birds, insects, small mammals, amphibians, reptiles, aquatic species and more. City planners can develop policies, such as zoning regulations and building codes, that protect biodiversity and limit harm to species.

For example, public authorities can diversify the native species of plants and trees used in public spaces and they can require developers to include green roofs or green walls in their building designs. Native plant species, adapted to the local climate and soil conditions are effective at providing habitat for native wildlife.

Incorporating green spaces, such as parks, gardens and street trees into urban areas can provide habitat for wildlife and support biodiversity. Green infrastructure may help to mitigate the effects of climate change, such as reducing the urban heat island effect and improving air quality and other environmental conditions – important social benefits, especially for lower-income urban residents.

Within the urban core, light pollution has become a critical problem for biodiversity. Outside of the city in a place without ambient artificial lights, one can see 3,000 or more stars in the sky. In a dense urban core that number can be less than 50. Globally, artificial light is increasing by 2% annually based on satellite imaging data, almost all of it concentrated in cities. Artificial light changes the behaviour and physiology of a wide range of species, dramatically reducing survivability and reproductive output. The swift transition to LED lighting for energy efficiency is a potent example of how technology can fulfill emerging priorities for energy efficiency while exacerbating the increase in nighttime illumination that affects biodiversity.

City-wide dimming of nighttime lighting, as Cambridge Massachusetts currently does, reduces sleep disruption and helps nocturnal species in their activities. Reducing light pollution by using shielded streetlights and overall reductions in the use of artificial light at night can help to preserve the natural behavior of nocturnal animals and generally protect the circadian rhythm for all species. For some species, insects especially, deploying new lighting technologies at specific spectral frequencies that are less disruptive of nocturnal behaviours should be further developed and deployed.

The notion of a wildlife corridor also pertains to the skies. It has been shown that bats, for example, are more likely to travel along dark routes and are therefore affected by the fragmentation of areas by artificial lighting. Even plant species can be affected by artificial lighting through changes to growth rates, flowering and overall physiology with consequences for pollinators and herbivores. For these reasons, light pollution needs to become a major priority for all cities hoping to contribute to the protection of biodiversity.

Urban water within cities can also be redesigned for positive biodiversity results. Implementing stormwater infrastructure, such as rain gardens and bioswales to manage stormwater and runoff, limiting flooding while also providing habitat for wildlife. In addition, the use of permeable pavement everywhere contributes substantially to improved hydrological flows.

Incorporating urban agriculture into city planning can provide habitat for pollinators and other wildlife while also providing food for urban residents. Systems can be as simple as rooftop farms which can be found in many American, European and Asian cities including Singapore as the exemplar, and as sophisticated as entire multi-storey buildings that act as superefficient and productive urban food factories of the nascent field of urban agri-tech.

All of these strategies are synergistic with the important concept of the walkable city. Originally described in the 1960s by the American urbanist Jane Jacobs as accessibility to amenities by foot, walkability has become a multifaceted strategy for reducing urban transportation energy and greenhouse-gas emissions, air pollution, improving health outcomes and reducing obesity and generally contribute to a city’s livability.

The notion of a ‘15 minute neighbourhood’ that promotes sustainable transportation such as walking, biking and public transit to reduce the number of cars on the road and minimise the impact of transportation, a diversity of housing types of different sizes to accommodate many types of households and a range of income levels, a mix of critical amenities such as food markets, healthcare, education, retail and hospitality, co-working spaces and smaller offices, and even light manufacturing holds enormous potential for advancing protection and enhancement of urban biodiversity.

Cities could become less like extended and homogenous grids of dispersed services and amenities and more like agglomerations of cells, rich in resources, resilience and biodiversity. Walkable neighbourhoods linked by good public transport corridors designed to protect and expand ecosystems and important habitats would form the structure of polycentric urban regions, productively connected to the hinterland.

Recent successes in rewilding – the reintroduction of native species – and enhancements to biodiversity at the four scales already described should be a motivating lesson for individuals and organisations interested in improving biodiversity on Earth. The role of education is important in empowering individuals, families and communities to engage in practical actions in their cities. In particular, community events for planting native trees, clean-up days to create awareness and generate interest, especially in the very young, are essential in driving momentum for a future of biodiverse cities.

The natural world is resilient and always opportunistic to find ways to flourish – even in cities. We just have to give it a fighting chance through initiatives like the World Economic Forum’s Biodivercities by 2030. We know that cities can play an important role in biodiversity enhancement. We now have to act to make that happen.

John E Fernández is director MIT Environmental Solutions Initiative and professor MIT Department of Architecture. Thomas Wiegelmann is managing director of Schroder Real Estate and honorary professor at UCL Bartlett School of Sustainable Construction