How well-suited is investment in UK social housing for institutions? Research suggests it can be a good fit for both debt and equity investors, writes Nicholas Colley

The UK residential rental property market has experienced a significant rise in interest from institutional investors over the past 10 years. Our research into social and affordable housing suggests the sub-sector’s attributes particularly justify its inclusion in a diversified portfolio that seeks to achieve strong and stable risk-adjusted returns.

The social and affordable-rented sectors account for about 20% of total housing stock in the UK, with private-rented housing accounting for a further 15% and owner-occupied housing 65%. Given that the social and affordable housing sector is a regulated activity, operators are required statutorily to be registered providers (RPs) and satisfy criteria set by the Regulator of Social Housing. To allocate to the sector, therefore, an investor needs to provide capital to an existing RP and/or operate via a new for-profit RP to help fund the new supply of homes.

RPs account for about 20% of annual completions – across all social and private tenures. Today, about 70% of capital is sourced from private financing, up from 30-40% in the 2000s. Privately-financed social/affordable housing clearly has a critical role to play in solving the under-supply of housing in the UK – and as detailed below, its cash-flow and other characteristics make it a compelling asset class for investors.

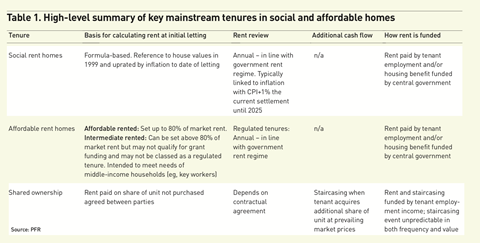

Whether investing via equity or debt, understanding the risks of underlying cash flows is fundamental to pricing the required return for an investment. Within the social/affordable housing sector, there are a range of tenures with different bases for calculating rent, reviewing rent and funding it (table 1).

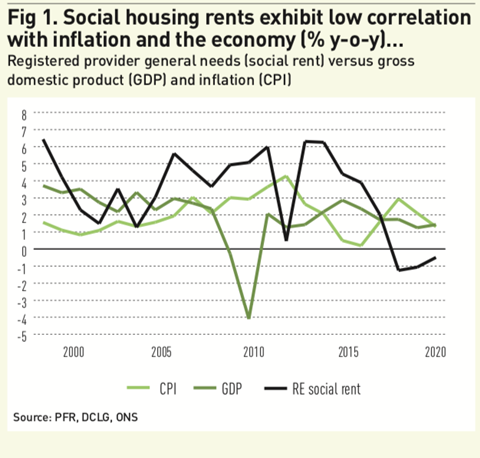

Because regulated social and affordable rents are subject to government rent-setting regimes rather than being driven by market forces, they tend to demonstrate lower correlation to short-term economic conditions than rents in other segments of the market. However, given the reference to inflation in the rent-setting regime, rents should be positively correlated with long-term inflation trends.

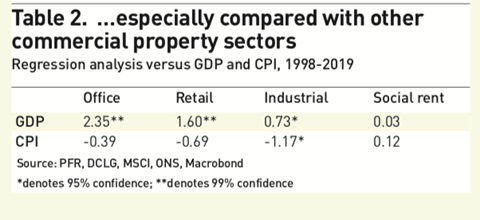

For example, figure 1 shows the average year-on-year growth for general-needs social rent (let by RPs) between 1997 and 2019 versus inflation (CPI) and economic growth (GDP). The relationship of rental values for this segment to the business cycle is negligible, with a beta to changes in GDP of 0.03, as shown in table 2. This compares to a beta of 2.4 for UK office rents (for every 1% change in GDP, office rents would be expected to rise/fall by 2.4%), 1.6 for retail and 0.7 for industrial rents.

This indicates that the cash flows (rents) generated by social housing can provide investors with effective risk diversification, especially compared with other rental sectors whose cash flows are more intrinsically linked to the wider economy.

Attractive occupation profiles

Another key metric for assessing income quality is the average length of occupation. This is not the same as the average lease length – which refers to the length of a contract – but the amount of time a tenant remains in occupation of the same unit. Compared with private-rented housing, tenants in the social-rented sector typically have much longer residencies. According to the DWP Family Resources Survey, 80% of social-rented tenants stay for at least three years in the same unit, while 44% of tenants remain in the same unit for over 10 years compared with just 10% of tenants in the private-rented sector.

The social-rented sector also has low and stable vacancy levels, with less than 1.5% of stock vacant over the past five years. This is not surprising, given the sector’s supply-and-demand imbalance: waiting lists of households for social housing in England have consistently been above 1m since 1997.

The implications of these two factors for quality of rental income from social-rented assets are:

- The sector has greater stability in rent levels, which are also not pro-cyclical;

- Gross-to-net leakage from costs associated with tenant turnover is lower.

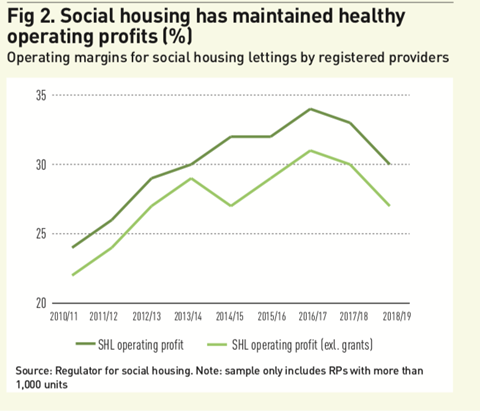

These characteristics support the view that the sector has relatively robust, higher-quality cash-flow fundamentals that should be attractive to both equity and debt investors. Looking at published annual accounts for RPs, we can see how this translates into operating profit for social housing lettings. As figure 3 shows, operating profits have been remarkably stable and healthy for the sector as a whole, averaging 30% (27% excluding government grants) since 2010.

The sector has fared significantly better than commercial real estate in rent collection during the pandemic, with the sector reporting collection rates of about 98% for both Q2 and Q3 2020, compared with just over 40% for retail, and 70-80% for office and industrial.

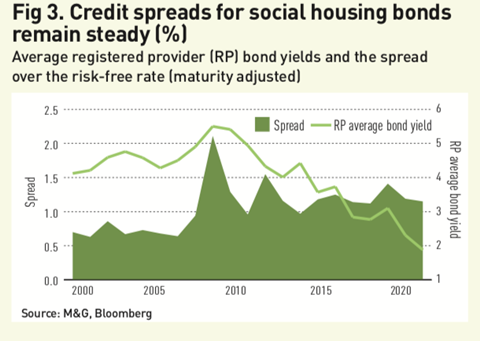

Private capital has been active in the social-rented sector for a number of years, primarily by providing debt financing via bonds. These have typically been issued by larger RPs with the scale and resources to access capital markets directly. Smaller RPs typically access capital markets via aggregators that issue bonds secured against a number of different RP assets. The credit rating for these bonds is typically single-A. The average maturity at issuance is high at 25-30 years, indicating that the duration risk will also be higher.

Investors in the sector have benefited from declining interest rates, with market values rising significantly as bond yields have fallen from 5.5% in 2010 to 1.8% by the end of November 2020. The credit spread also appears to be fairly constant post-2010, maintaining a weighted-average spread over UK governments bonds of typically 100-120bps (figure 3).

Although private-sector debt has increased as a source of capital to the sector, overall credit fundamentals have remained strong: interest coverage ratios (ICRs) have stayed at about 1.6-1.8x and net gearing ratios (NGRs) at 35-40% over the past five years. COVID-19 has had some impact on ICRs with the rate falling to 1.4x in June 2020 before recovering to 1.8x in September.

Public and private equity

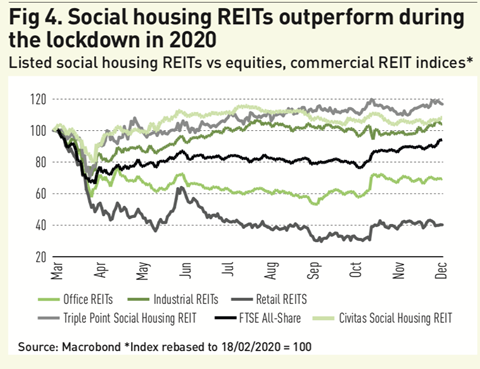

Public equity opportunities in the social-housing sector include specialist real estate investment trusts (REITs) such as Civitas Social Housing REIT and Triple Point Social Housing REIT, which have market caps of £650m (€736m) and £440m, respectively.

Historic performance of public equity is limited. But the performance of these two REITs during the COVID-19 pandemic versus REITs operating in other sectors suggests investors have recognised the particular stability of their underlying cash flows. Share prices for both Civitas and Triple Point have outperformed traditional commercial sector REITs and the wider FTSE All-Share Index since February 2020 (figure 4).

Private equity investment in social and affordable housing is growing gradually. A number of unlisted funds have been launched by asset managers, including CBRE Global Investors, BMO REP, Cheyne Capital, Man Group and Schroders. While a range of operating models between the funds and RPs exist, a typical model is to lease the homes to an RP on a full repairing and insurance basis for 20 years or more. We expect further innovation and differentiation in preferred operating models as the sector matures. A few asset managers such as Legal & General and Sage (owned by Blackstone) have opted to set up RPs themselves, giving them full ownership and operation of the underlying housing assets.

Investment in social housing assets is still in its infancy. But it might become increasingly significant for investors seeking stable and diversified cash flows underpinned by good credit fundamentals and with low correlation to other sectors.

This article draws on a forthcoming report sponsored by the Impact Investing Institute and Homes England.

Nick Colley is director at Property Funds Research

Social impact

The COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated the trend for impact investing in real estate, most notably in the area of social and affordable housing. In the UK, a growing number of funds have attracted pension-fund capital. While some of the scale and track record required by institutions was not available in ...

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

Currently

reading

Currently

reading

UK social housing: Investment case stacks up for institutional investors

- 6

- 7