With the word ‘recession’ increasingly on the lips of executives across the world, the energy crisis in Europe remains a key driving force behind the portent of an eventual downturn in the global economy. As Europe rapidly tries to wean itself off energy imports from Russia, decisions are being made in crisis mode, which are likely to bear long-term ramifications. To keep the lights on in Europe, policy officials are rapidly implementing policies which complicate an already bewildering environment for holders of patient capital, including investors of infrastructure, real estate and private equity who might have been banking on an agenda of decarbonisation prior to the Russia-Ukraine conflict.

Now, in the investment and corporate world, there is an evident tension between fiduciary duty and ESG commitments. For some investors and executives in the energy space, an elevated oil price environment and record high prices for natural gas have resulted in bumper returns and profits. On the other hand, for some executives relying on energy as an input – be it for manufacturing in industry or fuelling data centres in IT – the elevated cost of energy is eating into the margins of some corporations, potentially delaying previously made commitments to run their businesses on green energy, and thus raising the question of whether to pivot to cheaper sources of energy – such as coal – in the short to medium term.

And for policymakers, the prolonged energy crisis presents a true dilemma of balancing certain pledges to move toward net zero (some of which were perhaps promulgated optimistically when the world was on pause during the pandemic) with the present crisis-induced need to keep the lights on for households and companies – and thus to sustain economic growth and to deliver the social contract. Indeed, since the rolling power crunches of autumn 2021, leaders from across the globe have conflated the terms energy security, economic security, and national security, often using them to justify record imports of coal.

What does this volatile and complex landscape mean for infrastructure investors? While green governments are cementing 30-year contracts in natural gas, is natural gas investing off the table? What happens when this crisis eventually abates? Will holders of carbon assets – be it upstream, mid-stream or downstream – be branded renegades and punished for having sticky fingers? Where are the opportunities for investing, geographically and at the asset level? What can policymakers do to support direly needed investment in infrastructure assets across the board?

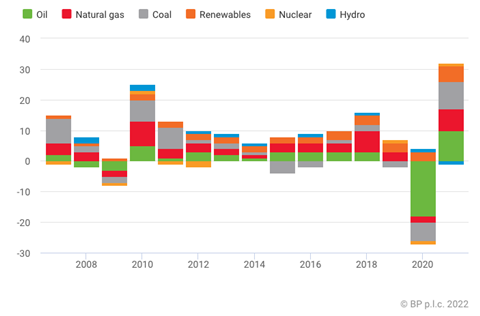

It is important to ask the question of just how we arrived at this dire juncture. In many Western (and oil and gas importing) countries, we had hubristically assumed that we had evolved beyond energy shocks. Moreover, amid expectations of a climate revolution, we had also pridefully assumed that we were rapidly moving beyond the use of carbon in the energy mix. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine – and the attendant disruption to global energy markets – have laid bare the halcyon tinge of such expectations. Indeed, as we can see in figure 1, despite trillions of dollars flowing into impact and ESG funds and climate investing, renewables still make up a slender (but growing) portion of the global energy mix, at 5%.

Figure 1: Change in global primary energy by fuel

The geopolitical landscape: sauve qui peut

While one of the root causes of Europe’s energy crisis – Russia’s invasion of Ukraine – has revealed a world of deep fragmentation, further ruptures within Europe are beginning to manifest. As Russia curtails flows of natural gas to Europe, pipeline politics are cropping up within the EU. Earnest commitments to connect northern Europe to pipeline gas to the eastern Mediterranean have been rebuffed, prompting one statesperson to decry that bilateral problems are no longer bilateral – rather, in the new age of ‘energy sobriety’, bilateral problems have multilateral repercussions.

As winter looms – when seasonal demand for natural gas increases for households and for companies – such ‘beggar thy neighbor’ policies might deepen and proliferate, potentially upending European cohesion and solidarity when it is needed most. Thus, International Energy Agency chief Fatih Biroh depicted a possible “wild west scenario” playing out within the next few months, should European countries cease to facilitate trade and to collectively address fuel shortages.

While much of the attention in global energy markets is currently fixated on Europe, the strengthening trade flows between the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries and Asia merit strong attention for investors across sectors. Indeed, even despite robust commitments to move toward net zero at gatherings such as COP26 and the G20, resource-hungry Asian countries including Japan, Korea, India and the Philippines continue to step up imports of crude oil and natural gas from countries such as Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Kuwait. Amid sky-high prices for natural gas, demand has also shifted from gas to oil for power generation – a feature that has the potential to push the price of oil past $80 per barrel over the medium term – and also support sustained flows of crude oil from GCC to Asia. Indeed, South Korea, which has recently paid the highest price for an LNG cargo from Egypt, continues to steadily import LNG from Qatar and has recently posted record imports of crude oil from Saudi Arabia.

In the event of a European recession, a collapse in external demand from European markets – and the potential for a ripple effect across other markets, such as in North America – might result in a contraction in growth in countries with deeper trade exposure to Europe, such as ASEAN countries (In 2019, the EU accounted for 10% of ASEAN’s total exports). Nevertheless, looking toward the medium and longer term, beyond the present crisis, manufacturing activity in developing Asian countries – including India – as well as demand for power generation in urbanised and advanced economies such as South Korea and Japan – will likely continue to underpin resource ties with the lowest cost sources of oil and natural gas in the GCC countries.

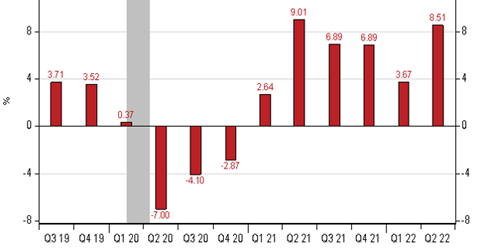

In turn, the sustained dislocation in global energy markets – the cementing of long-term contracts for natural gas from the UAE and Qatar to Europe, as well as to pockets of Asia – is likely to also generate corollary investment opportunities in exporting countries including the UAE and Saudi Arabia, across the infrastructure spectrum. One prominent investor has recently doubled down on investing in ports in the region, especially promising given the strong position of the GCC as a logistics hub with developing Asia, Africa and the Middle East. Additionally, despite posting a record trade surplus amid the lofty oil price environment, as we can see in figure 2, Saudi Arabia has also generated notable increases in non-oil GDP growth. With the offset from conflict in Russia, Dubai, Abu Dhabi, and Riyadh are also emerging as talent hubs – and continued reforms within Saudi are magnetising talent from across services sectors.

Figure 2: Growth in Saudi non-oil activities GDP (% YoY)

In scoping the horizon for long-term investment opportunities, investors would do well to consider the future of ‘climate tech hotspots’. Carrying on the theme of ‘blue today, green tomorrow’, several key cities still involved in the fossil fuel industry might naturally emerge as hubs for new energy. One observer points to Calgary, Singapore and Rotterdam as viable investment destinations. Abu Dhabi, Dubai and Riyadh also come to mind. With an eye on the future, venture capital is providing record funds for climate tech clusters, concentrated in key hubs – namely, Silicon Valley, Bangalore, Shanghai and Berlin.

In considering the landscape of investable assets in this new age of energy sobriety, it remains clear that we live in an energy transition, rather than a wholesale climate revolution. As such, a humble and grounded understanding of the enduring role of carbon in the energy mix opens up opportunities for investing in both blue and green hydrogen and ammonia, and also across the carbon tech landscape.

In the case of the former, Portuguese Prime Minister Antonio Costa has lauded the short and longer-term opportunities for the proposed MidCat pipeline to run from Iberia to Italy, which would channel gas today, and “tomorrow, green hydrogen”. Similarly, natural gas giant Qatar has launched the “world’s largest” blue ammonia project, while blue ammonia also underpins the new energy partnership between the UAE and Germany. Ahead of COP27 in Cairo, Egypt is also planning to spur the growth of a “green ammonia” hub along the Suez. Of course, as with any large-scale projects born of ambition, we must track those that actually come to fruition. Nevertheless, the transition from black to blue and green is emanating from across the energy landscape.

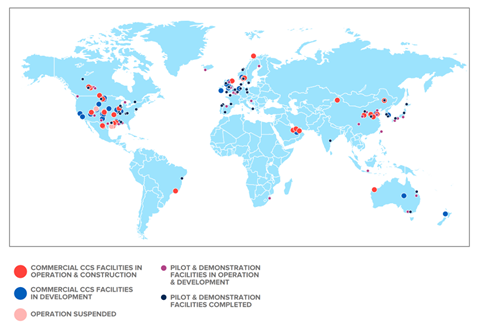

As carbon still plays a role in the energy mix, carbon capture, utilisation and storage (CCUS) is also a clear (albeit, perhaps less grand) investing opportunity. As we can see in figure 3, in terms of geography, the US takes the lead in CCUS projects, in part due to a generous system of tax credits for players in the space.

Figure 3: World map of CCS facilities at various stages of development

Climate tech and CCUS present a natural juncture for large institutional infrastructure investors to work in tandem with venture capital. Alternatively, for corporations and private equity, the opportunities in certain elements of climate tech offer compelling reasons to expand venture capital capabilities as well as portfolios.

Finally, given all of the policy attention on bolstering strategic reserves of energy – and recognising that we always fight the last crisis – the prospects for investing in energy storage are likely to remain bright for the foreseeable future.

De-risking assets for patient capital

In sum, recognising the enduring role of carbon in our new age of energy sobriety – as well as the potential for legacy natural gas assets to convert to blue and green, and the robust role CCUS has to play – governments should work to de-risk assets for holders of private capital. Indeed, while governments are cementing 30-year contracts for oil and natural gas, and fast-tracking the infrastructure to support these deals, infrastructure investors with a horizon of 10-20 years will likely need guarantees from overlapping authorities, be it at the municipal, provincial or federal level.

Governments are likely to be incentivised to do so, given that the pandemic-induced shock-and-awe fiscal stimulus which preceded the energy crisis has resulted in record public deficits, sitting atop an already deteriorated fiscal position within many advanced economies in the post-GFC world. In short, policymakers are tapped out of funding and will likely need to rely on the private sector to support their endeavours related to energy security, ideally preventing a tail risk for investors getting stung by ESG requirements down the line, as the crisis eventually subsides. COP27 in Cairo can present just such an opportunity for cementing constructive public-private partnerships, for governments to work responsibly with pools of patient capital, emanating from investors whose mandates span far beyond several electoral cycles.