Fears are growing about the next pressure point on US banks emanating from real estate, but in Europe the office sector is more resilient and banks are less exposed, writes Kim Politzer

European real estate is more defensive than its US counterpart. For one, there are tens of thousands of medieval castles across Europe, yet none at all in the US. And on a more sober note, the US commercial real estate market is weakening, with American banks exposed to the crisis via a record $5.31trn (€4.86trn) of total real estate loans and leases. Attention has quickly turned to the European real estate market – but here we believe the defences to be more impressive.

One factor is a marked difference between the US and European office sectors, exacerbated by the pandemic and the global shift to hybrid working. The return to the office has been much slower in the US. For example, based on subway exit data, the number of journeys made on the New York City Subway in February 2023 stood at 80.3m, still down almost a quarter from the 105.5m journeys in the same month in 2020, just before lockdown. By comparison in London, passenger numbers across the Underground and bus systems that month were down only 15% before COVID, according to Transport for London.

US office occupancy is also much lower than Europe at 40-60%, compared with 70-90% in the European market. Despite these lower occupancy rates, American companies haven’t cut the number of workstations they provide and the move to hot-desking seen in Europe has yet to happen: US firms still provide close to one desk per person (there are 96 desks available for every 100 workers), while in the EU there are only around 63 office desks for every 100 workers, the AWA Hybrid Working Index shows.

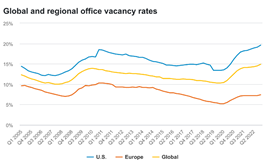

This has resulted in huge swathes of underutilised space in the US, and office vacancy rates are at 19.6% and rising, compared to around 7.4% and stable in Europe.

Nevertheless, US prime headline office rents have held up although landlords have had to increase tenant incentives significantly to make this work. Total incentive packages are now worth almost two years’ rent, with typical leases running for only five years. By contrast, European prime rents have risen moderately, and in some markets the use of incentive packages is falling away given shortages of good quality space.

The risks now present in the US market are exacerbated by the sheer scale of the buildings used to house offices there. Typically, these are large towers that cannot easily be converted to residential or other use. Their scale means that when building owners do give in and step away from their liabilities, the defaults are large. In February 2023, the Canadian real estate giant Brookfield defaulted on $784m of loans secured on two LA office towers. On the East Coast, one of the largest office building owners in New York, RXR Realty, announced that it was handing back the keys on at least two Manhattan properties. They reckoned continuing to make debt payments did not make financial sense against the backdrop of rising rates and the costs involved in repurposing them into economically attractive assets.

Banks’ exposure limited

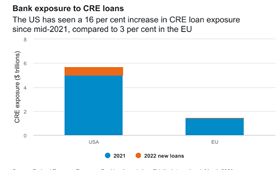

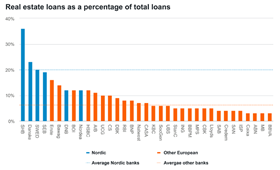

European resilience spreads beyond offices themselves. European banks are less exposed to the sector than their American counterparts. Commercial real estate lending makes up around 7% of European bank exposure; the figure is almost double at the larger US banks, at 13%, and six times larger – 43% – of the loan book of smaller and regional US banks. The latter have come into sharp focus since the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank.

Insurance firms are also highly exposed, with around 15% of life assurance funds held against investments in commercial real estate. According to JP Morgan’s Commercial Real Estate Overview, a loss rate of 8.6% to office exposure (based on a potential default rate of 21% and a loss severity presumption of 41%) would result in losses of $38bn in the US banking sector, and $16bn in the insurance market.

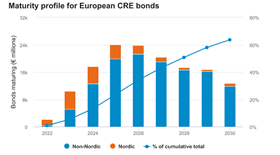

One final boost to the European situation is that many real estate bonds were renegotiated while rates were low and won’t need to be rolled over for some years.

Contagion risk remains

But as the countless impressive ruins that dot prominent spots across Europe testify, no matter how steep the ramparts or thick the walls, very few castles are completely impervious to outside forces. And the same applies to the real estate market in Europe. They could succumb if issues in the global real estate market worsen, triggering another liquidity crisis. Regardless of the relative strength of market fundamentals in Europe this could trigger a crisis of confidence across the whole sector. Tighter credit conditions for real estate would ensue, potentially offsetting any loosening of interest rate policy from central banks.

The European Central Bank identifies commercial real estate as a vulnerable sector and plans to strengthen its supervision of banks’ exposure to the market. An inspection of 40 banking groups last year found that commercial real estate can account for as much as 30% of banks’ non-performing loans (primarily legacies from the global financial crisis), while many bank lenders do not sufficiently monitor portfolio risks. Several lack commonly defined basic risk metrics at a portfolio level, occasionally not even understanding the location of buildings, according to the European Systematic Risk Board.

These weaknesses are feeding through from hypothetical risk to market events. At the beginning of March, Blackstone defaulted on a €531m bond backed by a portfolio of offices and retail owned by Finnish firm Sponda after bondholders voted against a request to extend the deal.

Indeed, the Nordics are the one region in Europe where banks’ exposure is comparable to the US, with commercial real estate loans accounting for more than a fifth of the loan book at Handelsbanken, Danske Bank and Swedbank.

Despite these threats, we don’t think it’s time to man the defences, and real estate may be more resilient than feared. There is still plenty of dry powder in the global system (currently around $469bn, equivalent to around two quarters’ worth of global investment activity). And we have seen surprisingly positive levels of liquidity across the real estate market, with one German asset attracting more than 20 bids in a recent sale.

The risks in the European market – and to European lending banks – are limited. Global commercial real estate might be under siege right now, but the moat around European real estate offers considerable protection.