Global ESG benchmark GRESB has nearly doubled its workforce in two years. In an interview with PropertyEU, the Amsterdam-based firm explains its structure, the reason behind its growth story, and a series of a new tools and initiatives.

Whether spurred by the pandemic, last year’s COP26 climate summit in Glasgow, or the wave of regulations sweeping across the industry, the drive to decarbonise buildings and cut their energy footprint has gained a new urgency.

‘Net zero’ has become the buzzword as property investors, owners, developers and asset managers set ambitious carbon reduction targets in line with the Paris Climate Agreement and United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. They are pushing the ESG agenda not simply to help cool a warming planet, but also because business success depends on it. Having the right sustainability credentials means a ‘greenium’ for assets, better access to capital, and a competitive edge in the market.

For investors and asset managers, the key to achieving their ESG targets is measuring the energy use and other sustainability aspects of their existing portfolios as well as assessing the future climate adaptation risks of newly acquired assets. This ‘need to measure’ has spawned a dizzying array of standards, benchmarks and reporting frameworks, against which a host of sustainability metrics can be assessed.

Demand for ESG performance data has surged, and for the providers of that data it has become big business. Behind the scenes, they are processing reams of data to score companies and portfolios, and to set benchmarks and standards in a fast evolving industry.

Amsterdam-based GRESB, a global sustainability benchmark for real assets established in 2009 and one of the pioneers in the field, has experienced this growth at first hand. Its workforce has nearly doubled in the past two years in response to the rise in demand. ‘We entered the pandemic with 30 people and now we have 50,’ says Anna Olink, business development director for the EMEA region, who herself joined GRESB last year from Kempen Capital Management, where she was a senior portfolio manager for real assets.

Investor-driven demand

The main driver of growth, she says, is regulation, and linked to that, investor demand for data. Investors are under pressure to tackle the effect of ‘brown discounting’ on their portfolios, amid increased sustainability reporting and accountability requirements. ‘Regulation is driving investor demand to understand what to invest in,’ says Olink.

This, in turn, is spurring fund and asset managers to have their properties scored and benchmarked in order to attract investment and see how they perform versus their peers.

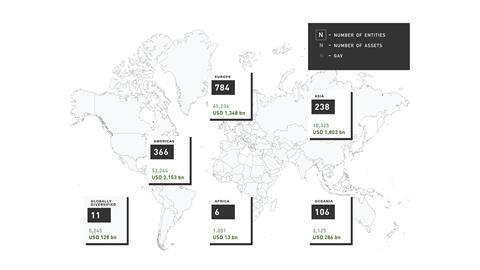

GRESB, a commercial provider which describes itself as ‘investor-led’, measures the ESG performance of individual assets and portfolios based on self-reported data. Last year, it saw participation in its real estate benchmark climb by 24% to 1,520 entities worldwide, the highest percentage increase since 2012 and the highest ever rise in total numbers. ‘This meant that nearly 117,000 individual real estate assets across 66 countries were reported to us,’ says Olink. In value terms, total AUM covered by the benchmark grew to $5.7 trn (€5 trn), up from $4.8 trn in 2020.

Much of last year’s growth was booked in GRESB’s home territory Europe, which saw a massive increase for the second year in a row and now accounts for nearly half the entire benchmark. Participation increased in Germany, the UK and Italy in particular, says Olink. ‘Growth in Italy was especially strong,’ she notes, with participation there leaping by 330% to 73 entities.

Thanks to a sustained investor push, overall participation numbers have snowballed in recent years and now include some of real estate’s biggest asset and fund managers. Says Olink: ‘We bring all the leading investors under one roof; they want to see a standardised ESG reporting method across all the companies they hold, so they send benchmark participants to us.’

Race to net zero

Despite these gains, the race to achieve net zero emissions will require a mammoth effort by the industry, for which, according to Olink, mindsets will need to change – and fast. Decarbonisation targets in Europe mean that by 2030, all new buildings have to be net-zero carbon in operation, and by 2050 they need to be net-zero carbon across their entire lifecycle (including embodied carbon).

As for the large pool of existing assets, these have to be retrofitted to be energy-efficient by 2030 – or well on their way to achieving that.

‘Many real estate managers don’t understand at all that they have to decarbonise,’ she says. ‘But that realisation has to be there, awareness has to increase and it has to increase fast, because 2030 is around the corner and 2050 is actually not that far away either.’ She adds: ‘In 2021, only 15% of participants reported that they had net zero targets in place, and 25% of companies did not have targets at all!’

GRESB, says Olink, has an important role to play in accelerating the effort. ‘We have to lead the market; by showing companies how they compare to their peers, it provides them with an incentive to act accordingly.’

A key part of this ‘facilitator’ role entails helping fund and asset managers with the barrage of ESG regulations sweeping across the industry. ‘The market is in a state of flux. The level of regulation is intensifying, and there are also a lot of new standards popping up, which we are incorporating into our services,’ says Olink.

New regulations

Among the wave of new regulations GRESB is aligning with is the EU’s Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR), the recommendations by the international Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD), and the decarbonisation pathways set by the Carbon Risk Real Estate Monitor (CRREM).

It has also developed a Transition Risk Tool showing companies which of their assets are most exposed to climate-related transition risk and how this might affect their portfolios over time – at both a country and global level. (see box below on ‘Alignment with ESG regulations’).

The growing range of services and tools and the ongoing evolution of its flagship benchmarks are a far cry from GRESB’s beginnings more than a decade ago. Says Olink: ‘We’ve come a long way since 2009; we’ve moved from excel spreadsheets to an online platform, from just three to around 150 investor-members, and from a dozen to more than 1,500 benchmark participants.’

The provider has also gained a new ownership structure following a management buyout in 2020, and is now a private firm with a commercial division for its benchmarking business and a non-profit foundation to govern its standards.

Five-year roadmap

But as the ESG train hurtles on, GRESB has reached a crossroads in its own development. The fund rating firm has launched a process to define its future direction and to ensure it remains relevant to the industry.

Last September, it kicked off an 18-month stakeholder engagement process to get feedback and collaboration on a five-year roadmap that will determine future ESG standards and milestones for GRESB assessments. The input gained will be used to inform what the GRESB assessments and benchmarks look like starting in 2024. A major challenge will be how to keep the reporting burden manageable as ESG regulations proliferate and require evermore granular data.

‘As the benchmark has grown year by year, the questions have become more complex, which can require more time to complete,’ says Olink. ‘It’s one of those inverse relationships whereby the reporting burden may become heavier as it’s become more useful. The scope of our survey is still the same, we still look at all the ESG topics, but we look at them in a more complex way. So, we’re at a point where we really need to make sure we are keeping in line with what the industry wants and needs.’

One-stop shop

On a practical level, GRESB is working to streamline its tools and processes, and has to that end expanded its inhouse team of digital specialists and data scientists.

On the scope side, the benchmarker is keen to ensure its standards continue to align with relevant industry frameworks such as regulatory requirements and reporting standards. The idea is to be a ‘one-stop portal’ where companies can go to have all their ESG reporting requirements serviced. Explains Olink: ‘If you’re going to take the time to do the main GRESB assessment, you’re already halfway done with your SFDR procedure and you’re also able to very easily get a transition risk report based on the info you’ve already provided. So it’s a question of: how can we make it a plus-plus value for participants so they don’t have to go through the whole process again on some other platform in some other way.’

Since many of the larger, overarching global ESG standards and benchmarks are not industry-specific, GRESB is eyeing a role whereby it can ‘plug the gaps’ to make them applicable to real estate. Says Olink: ‘There’s a lot of overlap but there are also going to be gaps where primary standards won’t be able to reflect the nuance of real estate, so we can kind of play that intermediary role.’

Olink says the ‘S’ and ‘E’ of ESG are also likely to gain importance as reporting metrics. ‘We are probably going to expand our survey further and broaden topics like diversity, equity and social inclusion, health & well-being, and human rights. That’s so important, and these are aspects our members identified as those we don’t put enough focus on at the moment.’

GRESB, she adds, is even thinking about how to structure questions around biodiversity and cybersecurity. Progress against net zero targets is also expected to be strengthened further. ‘So, the number of subjects is growing and the detail in terms of questions we ask is also growing.’

Industry dialogue

To ensure GRESB remains ‘future-proof’ and relevant to the industry, gaining input and support from its ‘stakeholders’ – not only investors but also asset managers, industry bodies and standard setters – is crucial.

Says Olink: ‘Before, it was always the investors who called the shots, they were the ones deciding what ESG aspects should be checked and what direction the survey should be taking.’ Now, she says, the emphasis is far more on collaboration between investors, asset managers and the industry at large.

‘Investors want superior risk returns – they use the ESG information for capital raising, stakeholder engagement, for valuation purposes etc. But benchmark participants actually run the business, they know what is feasible in terms of what is collected and in what way. So, we encourage dialogue between the investors who know what they want to see and the participants who can provide input on how things should be structured to make them practical. And we also involve experts in the field to help us find ways to appropriately evaluate aspects we want to include in the survey.’

************

Feedback from the field – what the industry thinks

GRESB has gained a broad following in the industry over the past decade, and counts some of the world’s largest institutional investors and asset managers among its backers and users. But why do they use it, and how does GRESB compare to other ESG benchmarks?

PropertyEU polled a few industry leaders to get their feedback. Global investment firm Hines, which has participated in GRESB since 2017, says it uses the GRESB Real Estate Assessment to measure ESG performance and identify areas for improvement across a series of investment entities.

‘It is particularly helpful in revealing areas where we want to sharpen our pencils even further to retain our market-leading position,’ says Daniel Chang, head of ESG – Europe.

‘GRESB is also a very comprehensive tool that helps us to communicate with our investors on our ESG performance, comparing our performance against that of our peers.’

Hines has been named a sector leader for the last five consecutive years for the Hines European Core Fund (HECF), and in 2021 received several recognitions: Overall Global Sector Leader, Global Sector Leader, Overall Regional Sector Leader and Regional Sector Leader. In addition, the Hines European Value Fund 2 (HEVF 2) and the firm’s separate account, the BVK High street retail mandate, were designated Overall Global Sector Leader and Global Sector Leader, respectively.

Hines also reports against the Global Reporting Initiative ‘to benchmark our progress and keep goals top of mind’.

‘We have become a signatory and made significant efforts to align to the United Nations Principles for Responsible Investment, while assessing the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosure and the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals for future disclosure,’ explains Chang. ‘These are quite different to GRESB as they address the components of ESG through different lenses and, notably, are less able to produce a score or ranking in relation to peers.’

Although not a benchmark, Hines has also joined the UKGBC, the British arm of the World Green Building Council network, to help ensure that initiatives focused on reducing carbon emissions and fostering social equity across the built environment are embedded into its approach to real estate.

Asked what the reasoning is behind participating in various benchmarks and initiatives, Chang says: ‘ESG is a broad area and so naturally there are benchmarks that report against different aspects of it with some having a focus more exclusively on progress made against environmental targets such as utility consumption as well as CO2 emissions, water and waste reductions, rather than potentially on progress with social aspects.

‘Many companies will participate in different benchmarks to understand how they are performing in more specific sub-sectors. However, too many standards can dilute how the industry achieves some of its goals and there is an argument for less labels and a need to merge some of the existing benchmarks.

GRESB, he says, is the largest growing benchmark of its kind, and, ‘although there is always a level of subjectivity, it is the closest benchmark in allowing a clear contrast between the performance of one fund to another and is a strong indicator of progress within the field’.

Ecore initiative

German fund management giant Union Investment is one player that has opted not to participate in GRESB, citing national legislation and its own scoring initiative ECORE.

‘We are pursuing our “Manage to Green” strategy and the goal of climate neutrality in the real estate portfolio by 2050,’ says Jan von Mallinckrodt, Union’s head of sustainability. ‘For this reason, we are placing an increased focus on national legislation and regulatory requirements at an EU level. In concrete terms, this means taking into account the climate path (Paris readiness) and also compliance with the requirements of the EU Action Plan (e.g. Taxonomy).’

To measure progress against targets, Union has developed its own ‘atmosphere’ sustainability label, which it says is open to other companies to use and has the potential to become an industry standard. The atmosphere scoring system forms the basis of the ECORE initiative, short for ESG Circle of Real Estate, which Union Investment has developed in tandem with other portfolio managers.

Von Mallinckrodt explains: ‘As part of the ECORE initiative, a globally applicable sustainability standard is being developed together with over 100 other market players, which takes into account the definition of sustainable financial investments (taxonomy) of the European Union and the goals of the Paris climate protection agreement and enables a benchmark. Many of these main arguments (e.g. the climate path) are not taken into account in the GRESB rating.’

Change in methodology

Another German heavyweight, residential landlord Vonovia, has not participated in the GRESB benchmark for the past two years, citing changes in methodology which require participants to report more granular, asset-level data. In an open letter published in July 2020, the company said the shift to an asset-level approach in that year meant that reporting data was ‘technically not possible’ for its 60,000 assets, and that aggregating data to clusters (e.g. city level) would have resulted in ‘meaningless or potentially misleading information’.

In a statement issued in March 2021, the listed company said: ‘We had hoped to find a way together with GRESB to enable large residential owners to participate in the survey in a way that was both practical and useful for investors. However, we have been informed by GRESB that a decision was made to postpone the proposed assessment solution for residential real estate managers.’

It added: ‘Unfortunately, this postponement means that compared to 2020 the framework for residential companies has not changed, and, as a consequence, Vonovia will not be able to participate in the 2021 survey.’

Nonetheless, Vonovia said it remained keen on participating in the GRESB survey in future, ‘as we are aware that it serves as a crucial source of information for real estate investors around the world’.

European shopping centre group Unibail-Rodamco-Westfield (URW) also paused participation in the GRESB assessment last year, citing the impact of the Covid crisis which, it said, had led it to focus its resources ‘for now’ on internal ESG performance management. It said: ‘This decision will be reassessed in future years, as the group remains strongly committed to transparency on its ESG achievements.’

**************

Alignment with ESG regulations

GRESB aims to align with key industry frameworks and widely adopted reporting standards, drawing on the most commonly used ESG metrics.

Among EU regulations it is addressing is the Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR), which requires asset managers to report detailed product and entity level ESG characteristics starting in 2022. GRESB says its SFDR Reporting solution will help enable real estate and infrastructure managers to meet part of their SFDR requirements, using a large part of the data already submitted in the GRESB Real Estate benchmark.

‘The questions that are already being asked in the GRESB survey overlap significantly with the questions asked by SFDR,’ explains Olink: ‘SFDR focuses on collecting granular, asset-level data, but that’s what we’ve already been doing ourselves. So, it’s an overlap that we are building on to and offering to existing participants as a tool but also as a standalone product.’

Where there are gaps in the data provided, GRESB makes estimates using its global real estate asset dataset, something it believes gives it an edge over other benchmark providers. Says Olink: ‘Because of the huge volume of real, validated data we have, when you need to estimate something – and SFDR allows estimates – our picture is much truer, because we can compare an asset that is missing data against a highly representative sample of assets that we do have data on. That makes our SFDR tool unique versus other products in the market.’

Another initiative GRESB is interfacing with is the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD), which aims to increase the clarity and relevance of climate-related information in corporate disclosure efforts. While the TCFD’s recommendations were originally voluntary, a number of countries are looking to make TCFD reporting mandatory.GRESB is developing a TCFD Alignment Report to help companies understand their climate-related processes, which it expects to launch in the course of 2022. As with the SFDR, much of the data already reported to GRESB can be used to check alignment with TCFD, ‘because we’ve been using the TCFD recommendations as the basis for many of the questions in our own survey’, says Olink.

Also in the area of climate change, the Amsterdam-based benchmarker is tapping into the decarbonisation pathways set by the Carbon Risk Real Estate Monitor (CRREM), an EU-funded research project which aims to accelerate the decarbonisation of the European commercial real estate sector by highlighting the downside financial risks of poor energy performance.

GRESB has developed a Transition Risk Report that shows real estate funds which of their assets are most exposed to climate-related transition risk and how this might affect their portfolio over time – at both a country and global level.

Olink explains: ‘The way it works is that companies report asset-level data to us regarding their energy consumption. Based on this data, we are able to calculate their GHG emissions and corresponding carbon intensities and show them their exposure to transition risk on an asset, country, property type, and portfolio level. So companies can not only see how they stack up against net zero commitments but also project when an asset will be at an increased risk of becoming stranded.’

GRESB is also monitoring developments around the EU Taxonomy Regulation, a green classification system that sets criteria for specific economic activities. The first stage of this complex piece of legislation came into effect in January and has significant ramifications for all AIFM companies that manage real estate funds.

*****************

How GRESB works

Established by three European pension fund investors in 2009, GRESB is used by more than 140 institutional investors to monitor the ESG performance of their investments, engage with their managers and make informed business decisions.

The portfolios of more than 1,500 real estate companies, REITs, funds and developers and more than 700 infrastructure funds and asset operators participate in GRESB assessments, providing investors with ESG data and benchmarks for more than $6.4 trn worth of assets under management.

The bulk of GRESB’s real estate participants are private companies. GRESB’s assessments produce four ESG benchmarks every year - for real estate, real estate development, infrastructure funds and infrastructure assets.

The assessments are based on what the industry considers to be ‘material’ ESG issues and are aligned with international reporting frameworks, such as GRI, PRI, SASB, DJSI, TCFD recommendations, the Paris Climate Agreement, UN SDGs, regional and country-specific disclosure guidelines.

The benchmark survey for real estate consists of three components: management (relating to leadership, policies and procedures, which accounts for 30% of the total score), performance (asset-level data for water, waste and GHG emissions, 70% of score) and development (design, construction and site development of new buildings).

The GRESB Score, represented as a percentage, gives participants insight into their ESG performance in absolute terms, over time and against their peers. Real estate participants can achieve Green Star status if they score more than 50% of the points allocated to each component. Participants can also be rated as a GRESB Sector Leader, GRESB Most Improved, or GRESB 5 star Rated in recognition of their leadership and commitment.

Asset managers self-report data, which is validated both automatically (for quantitative data) and manually (for qualitative aspects). Manual validation is carried out by independent certification body SRI. GRESB believes its self-reporting model makes it superior to rival benchmark providers. Says Olink: ‘We do have competition from entities that scrape the websites of public companies and they try to measure ESG progress based on that. But the accuracy and reliability of this data may not be sufficient for reporting requirements like SFDR. We don’t check anyone’s website to produce our assessment reports, we ask companies to answer our questions and to submit proof in our portal.’