Africa’s serious lack of sustainable infrastructure is generating huge investment opportunities. Christopher Walker talks to some of the first movers

Many of the biggest ESG infrastructure opportunities are in Africa. To meet the UN sustainable development goals (SDGs), the Global Infrastructure Hub estimates that $165bn (€146bn) a year of financing will be needed. A report from Rand Merchant Bank suggests that the cost of transportation in Africa is about 50-175% higher on average than in other parts of the world because of poor road, rail and port transportation infrastructure. In addition, the African Development Bank states that nearly half of Africans have no access to power.

These pressures are likely to increase. Sub-Saharan Africa’s population is projected to double by 2050, and Philipp Müller, CEO of BlueOrchard, says “this creates considerable demand for the development of infrastructure in an environment where local governments and other funding sources are far from meeting the growing demand”.

In addition, after the terrible experience of the pandemic in Africa, there is an increased focus on resilience spending on infrastructure. In a paper the OECD argues: “The pandemic is a reminder of our own fragility [and the] costs of a crisis may far outweigh incremental investment in resilience.”

The World Economic Forum, in article on resilience investing, concurs: “Institutional investors are […] seeking to strengthen the ESG metric, a gap that can be met by investments to prevent fragile situations from spiralling into crisis and to pave the road towards a sustainable economic recovery.”

There is also a geopolitical angle. As part of its Belt and Road programme, China has been investing heavily in African infrastructure, albeit without an ESG lens. Since 2000, the Chinese have supplied $6.5bn of finance for coal projects in Africa, seeking a tripling of coal output by 2060. China aims to expand the coal-fired Hwange Plant in Zimbabwe, taking coal production from 3m tonnes to 15m tonnes. The Ghanaian Government is also working with Shenzhen Energy to build a 7,000 megawatt coal power plant.

Apart from the effects on carbon emissions, ESG investors are concerned about the environmental effects in Hwange national park (home to half of the world’s elephants), and about working conditions in Chinese mines. This infrastructure spending has also trapped many African countries in huge amounts of debt. The World Bank’s chief economist Carmen Reinhart notes that 60% of Chinese banks’ lending is to developing countries.

European development finance institutions (DFIs) are showing a different, greener way. The Commonwealth Development Corporation (CDC) Group, the UK’s DFI, has invested £4bn (€4.8bn) in Africa since 2017, and its CEO, Nick O’Donohoe, says it will be investing £7.5-10bn in the next five years, continuing to focus on Africa.

O’Donohoe sees the G7 coming together to build more green infrastructure in Africa and Asia. There will be “a clear focus on climate resilience and finding nature-based solutions”, he says, adding that the CDC believes African “infrastructure is critical to raising productivity and competitiveness and improving the livelihoods of communities and cities across the continent”.

O’Donohoe continues: “Already, a third of our investments would constitute ‘pure infrastructure’ plays. The proportion that is infrastructure in the broader sense is much greater – indeed, you could say in many ways it is virtually our entire portfolio.”

As part of this green strategy, the CDC recently announced a $500m investment in African forestry, which is “a key step toward addressing the climate emergency”, says O’Donohoe. “The continent faces a growing wood products shortage as economies and populations grow.”

The CDC’s infrastructure investee partners include: Globeleq, an independent power producer with investments in Cuamba (Mozambique), Benban Solar Park (Egypt) and Malindi Solar Group (East Africa); Kenya-based Greenlight Planet, the leading solar-energy business in Africa; Liquid Telecom, the largest independent fibre and cloud provider in Africa, and its recently announced Gateway partnership with DP World.

The latter aims to invest $1.72bn in ports and logistics infrastructure across Africa. Holger Rothenbusch, CDC’s managing director of infrastructure, says Africa has a sixth of the world’s population, but accounts for just 4% of global container shipping volumes. “Ports are vital [but] in Africa remain constrained, lacking in capacity to meet the needs of local economies.”

The partnership will support modernisation across Africa, starting in the ports of Dakar (Senegal), Sokhna (Egypt) and Berbera (Somaliland). By 2035, an estimated $51bn in additional trade is forecast to pass through the ports, equivalent to 3% of Senegal’s GDP, 3% of Egypt’s GDP and 6% of Somaliland’s GDP.

Africa is also a priority for Roland Siller, the CEO of DEG, Germany’s new DFI. Co-financing with other DFIs accounts for about two-thirds of DEG’s investments. “I think it’s very important that we all put national concerns behind us, and cooperate more together,” Siller says. “Think of the impact we could have if we worked more together as a group – particularly in Africa.”

Siller has “seen what is possible in countries where the political governance has improved, and human capital has been unleashed”. He says: “The German government has a strong will to invest more in Africa; you’ve seen Angela Merkel’s initiative for Africa, inviting more German companies to get involved.”

“Infrastructure is critical to… improving the livelihoods of communities and cities across the continent” - Nick O’Donohoe

Since 2019, DEG has provided European companies with a financing product for investments in Africa through its ‘Africa Connect’ offering. Investments in reform-oriented African countries are specifically promoted and facilitated through a special model of risk sharing.

A question of risk

But does investing in African infrastructure pose too high a level of risk for institutional investors? Chris Leslie, global head of sustainability at Macquarie Asset Management, says: “Clearly, emerging markets offer enormous opportunities, but can present managers with fiduciary challenges.” But, Müller says, “emerging markets infrastructure is not as risky as you would think – in my opinion that is backward-looking”. He points to project-finance default and recovery rates published by Moody’s and Mercer, showing that many US projects are, in fact, higher risk than those in emerging markets. “In infra, of course, there are many risks, but there is much you can also do to mitigate risks.”

Hussein Sefian, the founder of Acre Impact Capital, agrees that “banks have been increasingly reluctant to get involved [in Africa] given the political risks in many developing countries, and the heightened lending caution [since the onset of the pandemic].” But there are de-risking solutions. “While export finance is a commonly-used mechanism for unlocking trade in goods and services in emerging markets, its potential to channel impact investments for essential infrastructure has been underappreciated – until now,” he says.

It has a particular application for the sponsors of infrastructure projects. Under OECD rules, they can benefit from reduced borrowing costs on 85% of the cost of a project if they attract the support of an export credit agency. The remaining 15% must be fulfilled privately and, to add to developers’ difficulties, the capital must be provided upfront.

Acre intends to launch a range of private debt funds to step into this sector. The company recently advised Investec, the Anglo-African wealth management group, on its investment in Ghana’s Western Railway Line. “This project is particularly impactful in reducing greenhouse gas emissions, as the new 100km of rail track will move a lot of trucks off the road,” says Sefian.

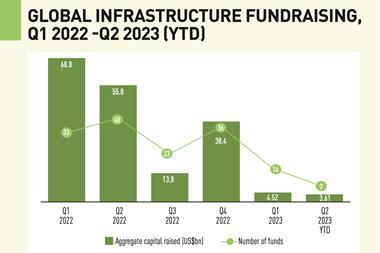

According to Preqin, Africa-focused private infrastructure assets under management increased to $44bn at the end of 2020, almost double the $24bn at the end of 2011. Yet, a lot of mainstream infrastructure specialists are sceptical.

Hamish Mackenzie, head of infrastructure at DWS, says: “Long-term stable investment returns… tend to be found in the more mature infrastructure markets. This is why we focus on Europe and North America.” Others feel the opportunity is too big for private capital to ignore. Müller says: “There exists currently an annual investment gap of approximately $2.5trn in developing countries, which needs to be bridged to reach [UN SDGs] by the target date of 2030.”

The BlueOrchard Sustainable Asset Fund aims to address “unmet needs in the market for sustainable infrastructure” in the areas of energy, river transportation and data. “We have been involved in a solar-powered telecom-towers project in sub-Saharan Africa,” Müller says. Projects “which are too large to be locally financed.”